Here you find:*

section 1: What, where, why?

section 2: When, how? the CMMM process (includes downloadable files of the CMMM book in 5 languages)

section 3: Who was involved?

* In the book version, these three sections together with section 4: Thoughts On... compose the introductory chapter.

section 1

CMMM is a practice-oriented research project that was designed to support civil society actors in their struggles for just societies and cities in the pursuit of profound political transformation. In their quest to change power relations, mobilisers in municipalist movements are continuously re-thinking and re-shaping instruments and mediums. In this project we focused on critical mapping as it constitutes an “act of power,” one that transcends theorization to establish different perspectives on realities, an action aimed at changing narratives and discourses.

The evolving democratization of mapping through new technologies is deconstructing it as an elitist instrument for the few and making it available to the many as a medium for (self-)empowerment. Maps are helping to give shape and size to issues that are hard to grasp, particularly complex issues at urban scales. Theoretically, we based our work on an exploration that K LAB conducted in parallel to this project, which is captured in the mapping change logbook, [1] regarding what constitutes critical mapping and what are its transformative potentials. In this practice-based CMMM project, we investigated the emancipatory claims of critical mapping through collaborative activities and comparative research on specific spatio-political issues in three cities: Barcelona, Belgrade, and Berlin.

These cities were chosen because of several factors, one being the variance in their levels of political organization and the achievements of the respective local municipalist movements. Whereas in Barcelona the contemporary municipalist movement managed to oust traditional parties from the mayor’s seat in 2015, in Belgrade they are just starting to make it to municipal councils (as of April 2022). Meanwhile in Berlin, in spite of the very rich scene of initiatives and activists, there is still no framework that contests the established political structures with an alternative. Other factors include points of divergence and convergence offered by these west, east, and northern European cities in terms of political and economic histories and contexts. In the second half of the twentieth century, all three cities were sites of complex socio-political contestation. Before neoliberalization swept through the globe, their spatio-politics were largely socialist and their traces still greatly impact the realities in these cities today, as shown in the timelines that were mapped in this project.

We understand critical maps within the broader definition of the term, to be encompassing of various kinds of visualizations and communication tools and, above all, the processes that give rise to them (i.e., not just the “output”). From this perspective and as outlined in the CMMM process, which spanned over 3.5 years from 2019 to 2023, our team of scholar-activists worked on developing methodologies and creating critical maps of multiple formats that support the agenda setting, claim-making, and communication of our collaborating collectives, initiatives, and civil organizations on the issue of the Right to Housing. This includes creating timelines of events and changes in legislations and using maps, posters illustrating relevant actors and processes, and custom-programed interactive online maps that translate the findings and needs defined in the analysis presented in the various sections of this work.

While we started off with a general vision and a set of targets that were outlined in the funding proposal we submitted to the Robert Bosch Stiftung, we allowed the process, the events around us, and the needs of our team members to influence the discourse and dictate the specific foci and shapes of our collaboratively produced outputs. Guided by feminist data visualization principles,[2] we were careful to not let the comparative scope of the project overshadow the differences between the teams. Therefore, the many sections of this work present varying rather than standardized inputs about the same topics. On another level, we took advantage of digital formats to allow readers to further explore the mentioned actors, events, or references via hyperlinks whenever possible.

[1] The mapping change logbook was the result of the postdoctoral project “Mapping for change? Critical cartography approaches to drive socio-environmental urban transformations,” which was conducted by K LAB between October 2018 and April 2022. It was financed through a grant from the Volkswagen Foundation under its program: “Original – isn’t it? New Options for the Humanities and Cultural Studies” (now OpenUp). It contains a selection of key findings from the project, including primary, secondary, and tertiary materials on concepts and experiments that engage critical mapping. For more information, please see Section 16: mapping change logbook.

[2] The six principles of feminist data visualization outlined by Catherine D’Ignazio and Lauren Klein are: 1. Rethink Binaries, 2. Embrace Pluralism, 3. Examine Power and Aspire to Empowerment, 4. Consider Context, 5. Legitimize Embodiment and Affect, 6. Make Labor Visible (Klein, Lauren F, and Catherine D’Ignazio. 2020. Data Feminism. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Mit Press).

Why housing?

At the outset of the project, our newly formed CMMM team chose housing as the thematic and comparative entry point. First, this was because it represents a common arena of suffering in the three cities. Second, it is a domain in which the members of our team were strongly invested. And third, back in 2019, it was clear that this basic need for dignified life would mobilize people to support endeavors for political change.

We understand housing as a broad term that transcends “having a shelter” and encompasses people’s concerns for daily sustenance. It includes aspects of adequate infrastructure and health care, access to education and non-monetized non-commercialized spaces of socialization (which is as central to mental health as water and clean air), and therefore, the systems of spaces that allow for just and secure social production and reproduction. By extension, the term should ideally also include spaces of labor and production, which have been dislocated from realms of housing by functional principles of city management. However, under current sectorial political paradigms, this extended meaning is hard to translate into policies of spatial governance.

Under this central theme, some of the comparative lines we saw at the beginning of the project were the issues of housing burdens (how much of a person’s income is spent on housing), evictions (active and passive models), touristification, and the financialization of housing (real estate having become a prime object of speculation by international corporations). In addition, across the three cities, we saw how the growing challenges related to access to affordable housing have triggered the formation of collectives and initiatives that work on alternatives. As the outputs of the project displayed here demonstrate, these topics were addressed to varying degrees in the respective activities of each city team in accordance with the characteristics of the locations and events that took place during the process. CMMM was an accompanying research project that operated in tandem with the activities of their collectives and organizations, as described in the section "The three cities in context: housing, municipalism, and CMMM."

“No vas a tener una casa en la puta vida”* [you will never have a house in your f***ing life]

“On the streets, people were sleeping huddled in doorways or under bridges and walkways, or sometimes in tents they had pitched on the pavement. Everyone walked past them, these reproaches to subjectivity, with apparent indifference.”**

* Slogan of a 2006 campaign by the V de Vivienda [H for Housing] movement, and it became part of the campaigns of the La Plataforma de Afectados por la Hipoteca – La PAH [Platform for People Affected by Mortgages] which was created short after, in 2009.

** Cusk, Rachel. 2023. “The Stuntman.” New Yorker, April 17. Accessed 5 May 2023. newyorker.com/magazine/2023/04/24/the-stuntman-fiction-rachel-cusk

After an unhoused New Yorker, Jordan Neely, was killed by a fellow subway rider on May Day 2023, a protest engulfed the city’s underground railway. In one of the videos that went viral, I was struck by the words of a protester who said that many people who showed up for the protest feel that they themselves are just a couple of steps away from being unhoused and with that in mind, they can identify with Neely and feel rage against the authorities who, at the time, were not prosecuting his killer. This comment, delivered as a-matter-of-fact, saddened me. How is it possible that secure tenure is unimaginable to so many people and yet, rage is triggered by identifying with the possibility of becoming unhoused, rather than through rage against the world that so casually condemns us to houselessness? Could this interpretation of ultimate housing insecurity be understood as a consequence of what we still call the housing crisis? And if so, does this crisis, which has permeated our collective narrative since the first decade of the new millennium, have an end?

According to Merriam Webster dictionary, crisis is “an unstable or crucial time or state of affairs in which a decisive change is impending.”[1] Following this definition, we can locate this “unstable or crucial state of affairs” much further in the past. The large-scale collective solutions to urban housing that were safeguarded by the mechanisms of the state collapsed during the last two decades of the twentieth century and gave way to the permanent state of crisis. The only solution that was offered was a liberal legal concept of equating security of tenure to individual ownership rights. This was coupled with the prevailing claim that sufficient amounts of housing can only be safely delivered through the market. Land titling and right-to-buy housing policies were designed to manufacture political consent for a neoliberal project all over the world and to enable real-estate markets to take over as much territory as possible. As Rolnik points out, the World Bank alone has executed more than forty projects in less than twenty years that were related to land regularization, titling and real-estate registration.[2] These projects were implemented in many countries, from Peru to Pakistan, redrawing property lines so that the urban land relations can neatly fall under the singular concept of ownership and thus fit into the financial market flows extracting value from reproduction via mortgage. Property lines were drastically redrawn even in places such as Berlin, where hundreds of thousands of public housing units were released for purchase and subsequently acquired by corporations. The UK, a bedrock of right-to-buy policy, transformed itself from a collective to an individual welfare state with housing privatization playing one of the pivotal roles in this shift. Investment in public or non-market housing has become just a miniscule fraction of what it used to be, and for the most part, public funds are redirected into subsidy schemes and tax benefits that promote homeownership. Local municipalities are nominally left with housing competencies, but without the sufficient budgets nor legal tools to genuinely intervene where needed.

This large end-of-the-century project redrew the political leverage that collective interest would have over the individual ones by redefining the role of housing as both a home and an asset, which is particularly challenging when it comes to organizing against housing precarity. This means that two people who are living in identical circumstances often have opposing beliefs of: being a few steps away from living like Jordan Neely; or being only a few steps away from becoming a small landlord.

The CMMM project and this book are a testament to how much effort and knowledge production goes into finding a common language within the city, and also how organizers are reshaping relations between cities by recognizing commonalities in struggles. It describes a relatively short period of time when major wins were achieved by the urban and housing movement, such as taking over the city halls or comfortably winning the vote in a referendum on expropriating corporate landlords. Such strides could not even be imagined just ten years ago, which proves that only collective organizing can offer us a glimpse into a more just future.

However, we have also learned that taking over the governing power does not trigger a profound transformation in power relations, nor does winning a referendum deliver us socialization of housing. As we can see in the case of lost legal battles for regulating the private property rights in Berlin and Barcelona, power still resides in the framework of the institutions whose reflexes are hard to re-design. In the case of Belgrade, there is clear evidence of how property relations that were produced by the right-to-buy policies of the nineties still serve to produce political consent. Regardless of the location, the power of landlords and landowners to perpetually speculate with the value of rent and land goes almost unchecked and never truly challenged in policy or political programs. That is, to borrow from Ursula K. Le Guin, the power of existing property relations “seems inescapable,” however, “so did the divine right of kings.”[3] Therefore, I wonder, should we reframe the housing question into the question of power and dominance of collective property rights over the private ones or should we just continue with discussing the models of housing provisions instead?

[1] Merriam Webster dictionary. merriam-webster.com/dictionary/crisis

[2] Rolnik, Raquel. 2019. Urban Warfare: Housing under the Empire of Finance. London: Verso.

[3] Le Guin, Ursula K. 2014. “Speech in Acceptance of the National Book Foundation Medal for Distinguished Contribution to American Letters,” New York, 19 November. Accessed 5 May 2023. ursulakleguin.com/nbf-medal

Local politics, grassroots institutions, and candidacies directly created and controlled by citizens are some of the elements now grouped under the term “municipalism.” Here and there, experiences of small residents’ organizations that simply want to “change things” through what is closest to them, and governmental political projects that want to renounce the “party” form—the large organizations structured under pyramidal discipline—are multiplying. Beyond any particular ideology, their aim is more immediate: to recover the original definition of democracy, in which those who govern and those who are governed are one and the same.

La apuesta municipalista [The municipalist wager], Observatorio Metropolitano (2014)

Municipalism is a slippery concept that takes on different forms in different places. In Spain, it was part of a climate that changed the political arena with parties like Podemos. In France, it is linked to citizens’ assemblies and has incorporated elements of the Yellow Vests [Gilet Jeune]. In the UK, it is seen as part of the Labour party tradition, where community wealth building projects—such as the so-called “Preston model”— are considered a continuation of the socialist municipalism that proposed acting “in and against the state” in the 1980s.[1] In Croatia, municipalist platforms are linked to various “right to the city” movements fighting against the privatization of public space in Zagreb or massive touristification in Dubrovnik.

However, it is possible to identify commonalities. While academic researchers have defined this “new” municipalist declination as “cooperative,” “emancipatory,” and “progressive,”[2] the European Municipalist Network characterizes it as a common political project that embraces feminist, ecological, and decolonial values, and as a project that seeks to defend social justice, self-governance, and the common good.[3] At the same time, municipalism is more than a program: it seeks to influence not only what is done but also how it is done. Municipalism aims to change the way public institutions make and implement decisions, and the way civil society participates in the production of the environment in which it lives.

Municipalism as a principle, a project, and a practice

Municipalism is hard to pin down because it is more of a direction than a situation. At its core, municipalism seeks to transform key political, economic, and social institutions: the nation-state, capitalist markets, and political parties. This transformation is supported by existing processes and draws on previous experiences of democratic decision-making, like in the assemblies that emerged in squares around the world in 2011, and forms of mutual aid, as the ones we have recently experienced during the pandemic. Municipalism also incorporates alternative economies from cooperatives, social syndicalism, or community economies in the form of exchange networks for the production of material and immaterial goods, services, knowledge, and care. Since such a transformation cannot be implemented under a single shape, strategy, or set of policies, the term “municipalism” is used to denote at least three different things: a principle of radical democracy; an egalitarian project that aims to intervene—directly or indirectly—in electoral politics; and a collective practice that seeks to produce an organizational form that is different from both institutional political parties and traditional social movements.

As a principle, municipalism takes democracy as its starting point, arguing for the ability of the inhabitants of a given territory to organize themselves and for their right to have a say in the decisions that affect them. Municipalism’s radical democracy is based on an idea of the municipal scale not as a local branch of the nation-state, but as an autonomous territory that is nevertheless not an isolated community but rather a connected entity that maintains an interdependence between different territories and scales. Such a local autonomy of localized yet interconnected territories is present in the European democratic tradition, from the Greek in the 5th and 4th centuries BC, to the Hanseatic League in the 14th and 15th centuries, or the French uprisings of the communes, of which Paris is the most famous but was not the only one.

As a political project, the aim of municipalism is the creation of a democratic, collaborative, livable, caring, and fearless city (see Atlas del Cambio [Atlas of Change], Figure 2). The shared municipalist agenda seeks to implement the principles of the right to the city through the protection of social rights (such as access to housing and care) and through the management of public resources (such as water, energy, transport) as common goods. Two important elements of this municipalist constellation are a technopolitical approach to participation where open-source digital platforms are tools to promote and enhance citizen’s participation; and, the recognition of feminism as an intersectional element that is integrated into all areas of government and as a radical democratic approach that questions who defines the city model, how the strategic decisions that determine collective action are made, and which objectives should be prioritized.

As an organizational practice, municipalism can be seen as a “method” for creating open and decentralized organizations with distributed leadership, as a practice that is able to involve and cooperate with very diverse actors while maintaining a commitment to the production of networked communicative practices. In the territories where there has been a mapping project of municipalist practices, it is possible to identify the specific elements of their methodology. For example, in Spain, civic platforms shared a methodological approach with collaborative programs, open primaries, crowdfunding of campaigns, and ethical codes. In France, the map made by the Actions Commune network identified municipalist actors through their open process of proposing candidates, the existence of a committee to guarantee the process, and the collective definition of the role of the candidates once, and if, elected.

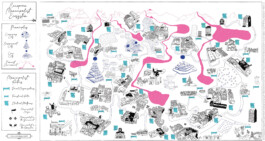

Figure 1.1

European Municipalist Ecosystem, 2021, by the European Municipalist Network, illustrated by Maria Gracía Pérez.

This map identifies established and emerging municipalist initiatives in different parts of Europe. The online archive, graphic representation, and a set of reports on different territories provide information about the actors’ goals and activities. municipalisteurope.org/mapping/

Figure 1.2

“Atlas of Change”, 2018, by the municipalist Cities of Change. This map is part of an online Atlas of municipalist policies and organizations, that seek to represent the “political geography of the municipalist change.”

The resulting archive is seen as a tool whose objective is to reflect the scope and diversity of the municipalist movement in Spain since 2015. It is intended to strengthen the network of cooperation, exchange, and construction of this political space, allowing for the accumulation of forces for the defense and vindication of social, political, economic, and ecological rights in our towns and neighborhoods. ciudadesdelcambio.org/mapa

Figure 1.3

“Actions Communes”, 2020, by Fréquence Commune. actions-communes.gogocarto.fr/

Challenges

Since 2011, democratic municipalism in Europe has experienced uneven growth, with municipalist platforms expanding in new areas and declining in others. At the same time, the sustained experience in places like Barcelona or Grenoble showed the potential reach and limits of municipalist politics. At the height of this phase, in 2021, three online events—the “Cities for Change Forum” organized by the City of Amsterdam, the international “Fearless Cities Summit” organized by Barcelona en Comú, and the EMN “Municipalist School and Feminisation of Politics” MOOC—addressed the role of municipalism as an emancipatory political proposal on a global scale. These events took place during the peak of municipalist international influence, which also coincided with the rise of far-right and authoritarian parties and the impulse given to national structures and policies during the pandemic.

Some of the challenges municipalism faces today resonate in the territories and projects presented in this book. First, the experiences of the Platform for People Affected by Mortgages (la PAH) and of the tenants’ associations (sindicat de llogateras) in Barcelona show the power of networked federalism, which allows for growth through connections rather than through expansion. The coordination of anti-eviction campaigns and citizens’ legislative initiatives links territories and problems that are already interdependent. In the CMMM project, housing is the connecting element between the city, the region, the country, and the continent. Second, AKS Gemeinwohl in Berlin is an example of re-politicizing the local, administrative level with an intermediary organization that seeks to mediate between the private, the public, and the collective. This municipalist strategy brings the demands, ideas, and sometimes activists of social movements into the plenary, while at the same time challenging pre-existing ideas about the concept of the common good, who defines it, and how it is implemented. Third, at last, Ministry of Space’s map of the impossibility of the rental market in Belgrade is part of an ongoing strategy to generate alternative presents (not futures): the creation of a map that looks legitimate, by an organization that sounds institutional, stands as a prefigurative intervention that seeks to persuade through the power of symbols.

This territorial and organizational diversity of situations, understandings, and challenges demonstrates the difficulty of providing an ontological definition as a template for what is or is not municipalism. Municipalism, however, defines a clear horizon of transformation through different paths, across different times and spaces. As such, it can be seen as a form of “vectorial politics,” better defined by the specific transformations—inside and outside organizations—that it seeks to achieve and the effective changes it produces. For this task, maps are strategic tools for visualizing the world not as it is, but as it could be.

Acknowledgements

This text is a personal interpretation of collective conversations and debates that took place at the “Fearless Cities” meeting in Barcelona (2017) and Belgrade (2019), during the “Urban Alternatives” mapping project and within the European Municipalist Network since 2020. Moreover, it incorporates an activist experience into the municipalist movement in Madrid and Spain since 2014.

[1] London Edinburgh Weekend Return Group (ed). 1980. In and against the State. London: Pluto Press

[2] See: Akuno, Kali and Ajamu Nangwaya (eds). 2017. Jackson Rising: The Struggle for Economic Democracy and Black Self-Determination in Jackson, Mississippi. Québec: Daraja Press; Russell, Bertie. 2019. Beyond the Local Trap: New Municipalism and the Rise of the Fearless Cities. Antipode, 51(3), 989–1010; García Agustín, Óscar. 2020. New Municipalism as Space for Solidarity. Soundings, 74, 54–67.

[3] See: European Municipalist Network mapping criteria: municipalisteurope.org/mapping/post/how/

Why critical mapping?

The three cities in context: housing, municipalism, and CMMM

Belgrade

Belgrade resembles other European cities when it comes to the manifestations of neoliberal urban development policies, including urban renewal, endorsement of private investment construction, financialization of housing, etc. However, the contemporary historical circumstances of transition from a socialist to a capitalist socio-economic system as of the 1990s after an ethnic war that dismantled the federal republic into six countries—along with its location at the periphery of the European Union on one side and Russia on the other—have made Serbia, and thus Belgrade as its capital, somewhat particular in terms of the scale and characteristics of such manifestations.

Figure 1.5

A residentail block in the New Blegrade district, the construction of which dates back to the socialist period. Image by Iva Čukić.

Belgrade is among the cities that have the highest percentage of privately owned housing units (over 95%). At the same time, it is estimated that around 80% of its people are struggling to access decent and affordable housing. While private investment in housing is growing and allowing for the wealthy to accumulate capital in real estate, inadequate housing conditions and evictions due to tenant indebtedness are becoming increasingly frequent, where many households are left without any housing solution or resources to provide an alternative. The predominant method to resolve one’s housing needs is through the market. Yet, the rising rents are quickly outpacing average incomes, which has resulted in a lack of affordable housing options for the vast majority of the population. As in many other large cities today, this situation has been exacerbated by Belgrade’s fast-growing numbers of short-lease rental units (due to platforms such as AirBnB), while long-term renters are finding themselves in precarious positions, forced to accept unregulated relations with their landlords.

In the past three decades, the state (under the control of the political parties, changed from center and to center-right) did not dedicate sufficient efforts to address this reality or collect comprehensive relevant data to obtain an overview and an understanding of the issue, nor did it articulate sustainable long-term measures to improve housing conditions. Housing is consistently treated as a mechanism for economic growth, rather than as a basic human right that should be safeguarded and made accessible to all. We explain these and other factors behind the housing injustices in Belgrade in Section 6 / BGD. Under these circumstances, it is necessary to first map the hierarchies and actors to fully grasp the scale of the housing crisis in Belgrade and in Serbia and then to reflect upon and advocate for systemic solutions—which are issues we sought to tackle through this CMMM project.

As the context in Belgrade is that of persistent crisis of democratic institutions and a lack of civic participation in processes of urban planning and development, municipalism has served as an adequate framework for urban activists. The only anti-establishment political movement is Don’t Let Belgrade D(r)own (Ne davimo Beograd, NDB), which emerged from the mobilizations against the large predatory investment project Belgrade Waterfront around 2015, which were largely initiated by the Ministry of Space collective. NDB positioned their program within the municipalist paradigm to promote more participation and the redistribution of power in the development and governance of cities, and their political program draws from and builds on the work of MoS. As a result of this success in the politicization of spatial governance, including housing, these realms are starting to attract more attention from traditional political actors as well.

We, the CMMM Belgrade city team, are members of the Ministry of Space (MoS) collective. Since its establishment, MoS has been concerned with the political and socio-economic dynamics of urban development and spatial injustices. As such, housing has been one of the focal points in our work. Together with other housing activists and relevant organizations, we have been fighting for a radical transformation in the city- and state-level approaches to housing. These include Who Builds the City (Ko gradi grad, which also initiated the regional network MOBA), A11 – Initiative for Economic and Social Rights (inicijativa za ekonomska i socijalna prava), the “Roof Over Our Head” joint action (Krov nad glavom), the European Action Coalition for the right to housing and to the city, and the International Network for Urban Research and Action (INURA).

The activities of MoS include conducting studies on alternative forms of affordable housing, disseminating knowledge on progressive housing solutions, developing policy proposals and strategic housing documents, participating in activist initiatives against forced evictions, and developing alternative housing practices. In this line of action, developing critical perspectives, research, and tools to re-think the realities on the ground have been deeply immersed in our methodologies and programs. Critical mapping, which has become a common tool in urban research, activism, and communication around the world, has been added to our agenda as well in recent years (e.g., the “Map of Action” (Section 8 / BGD) which we created and published in 2013, our contribution to the New Metropolitan Mainstream project from 2014–2016, our “Map of untransparent urbanism” project from 2017, etc.).

Soon after we started the CMMM project, the Housing Equality Movement (HEM) was established in summer 2020 to join forces and combine efforts to achieve structural change in Belgrade’s housing sector, which strengthened our position as MoS. We believe that the HEM has the potential to mobilize a wider public to exert tangible pressure on the local and national governments to shift the housing paradigms. Given the dominant political discourses, it is also quintessential to continue investigating and testing modalities for strengthening the collaboration between public institutions, activists, and professionals. Given the fact that the governmental units dealing with housing are understaffed and have very limited resources, the HEM sees itself as a knowledge mobilizer that compounds the existing knowledge in the civil sector, in academia, and in institutions and that ensures the involvement of various sectors of society. The AKS-Gemeinwohl model presented through the CMMM BLN team serves as a best-practice example in this regard.

CMMM was started as the COVID-19 pandemic was unfolding and restricting our possibilities. At MoS we braced ourselves for eventful years, the course of which could become a marker for Serbia if we could manage to influence the direction of the Master Plan for Belgrade 2041. Within HEM, we continued our work to influence the housing strategies that were being finalized and passed through legislative bodies. In addition, we continued our efforts to realize a pilot cooperative housing project with the help of the Standing Conference of Towns and Municipalities (SCTM) and to achieve a victory by winning the city halls back from the centrists and right-wingers in the upcoming general elections in 2022, as well as in those that followed.

Within the framework of the CMMM project, MoS sought to consolidate and connect research on housing in Serbia to support local struggles and political movements on the left. Therefore, we worked to map legislations, policies, events, and hierarchies related to housing in the city of Belgrade and their local and global roots and extensions to better understand how these are engendering urban segregation and housing deprivation—which can be found in Section 5: How did we get here? 3 x timelines; Section 6: Who decides on what? governmental structures, participation tools, and political movements; and Section 7: What are we up against? main factors behind housing injustice. Additionally, in Section 8, we share examples how to apply critical mapping in the field, and Section 13(2/2) contains an index of the major actors as part of an advocacy poster for the proposal of a rent control law, which is being led by NDM in 2023. In parallel to developing these materials, we conducted the workshops described in Section 10 and Section 11, which formed the basis of our interactive map “How (un)affordable is housing in Belgrade?” (Section 13(1/2)). This map is designed to engage personal scenarios in an easy-to-share format through social media.

Through the various materials and formats of this work, we provide information to support existing and future struggles that collectively push to create policy solutions and alternatives to integrate the “housing as a right” principle in political programs, long-term strategies, and legislation. We are dedicated to bringing back the legacy of collective responsibility for housing for all and thus to shifting paradigms and moving housing from its current positioning on the fringe of the economic sphere back into the social and political arenas. We are hopeful!

Berlin

In contrast to Belgrade, the vast majority of Berlin’s households, about 85%, are tenants. Their livelihoods thus depend strongly on the availability and affordability of housing units. The socio-economic and spatial conditions of Berlin as a divided city until 1989 created strong grounds for self-realization thanks to the abundant spaces and cheap rents on the one hand and the strong communities of socio-cultural alliances and initiatives on the other. This made the city attractive, a magnet for neoliberal investments after the reunification in 1990. The Reunification Treaty and related political arrangements saw to it that neoliberalism reigned freely in the city, providing the starting capital by selling off what used to be the assets of the former (east) German Democratic Republic and the perverse conception of the so-called Old Debts (Alt-Verpflichtungen).

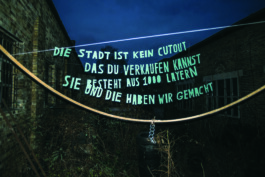

Figure 1.6

“Cutout” by prokura, an installation during the Reclaim Your City exhibition at Dragoner Areal, 2014. It says: “The city is not a cutout that you can sell. She is made of a 1000 layers that we made.” (CC 3.0)

As the current average rents remain somewhat lower in Berlin than in other European cities, investors claim that they should be much higher to achieve adequate return on investment in real estate. This narrative seeks to distract from the morbid living conditions for most residents in cities like Paris, London, and Barcelona. It overshadows housing policies and management discourses, and in effect it continues to reduce the supply of affordable rental units that are comparable to the levels of income of the majority of the population in Berlin.

Since the 1990s, the number of housing units held by state-owned companies has dwindled to about a third, although the population of the city has grown. As a result of the great mobilization of many civic initiatives around the issue of the right to affordable housing over the past two decades, as demonstrated in the Berlin timeline, the city is now trying to buy back some of this lost stock. However, large real-estate companies and the financialization of the housing market continue to set purchase prices beyond reach and raise rents disproportionately to incomes throughout Berlin. The result is the continued displacement of many tenants as gentrification takes over entire neighborhoods. We see this process as sacrificing housing as a human right, which should be countered by the Gemeinwohl-oriented governance of urban land and spaces. Gemeinwohl is a German term that is difficult to translate. It is a combination of public interest, common well-being, public welfare, and greater good. It is a central principle among the housing activists in Berlin, and thus it appears frequently throughout this work.

As mentioned above, Berlin is characterized by a very rich and diverse scene of neighborhood initiatives and civic action networks that have been working relentlessly to exert pressure on the political discourse, demanding that Gemeinwohl-oriented urban development be implemented on a larger scale rather than the current niche-scale. Some of the initiatives are testing and modeling new forms of cooperation between the city administration and civil society in an attempt to provide a new action base that is capable of countering the neo-liberalization of housing and urban spaces as well. In this context, between 2015 and 2021, the city administration regained its former role by applying legal instruments centered around the municipal right of preemption (RPE, also referred to as “right of first refusal,” in German: Vorkaufsrecht). However, a court ruling in 2021 repealed this instrument and has had grave consequences ever since, as explained in this work.

As the CMMM Berlin city team, we believe that whether Berlin remains livable and its urban spaces accessible for the many depends essentially on how successful both the civil initiatives and administration are in their cooperation to establish, institutionalize, and scale up principles and effective frameworks of Gemeinwohl-oriented urban development. This transformation must be planned and organized in different arenas and is subject to the course of negotiation processes. We are working on this using different methods and mediums, as organizers, artists, consultants, and activists in various groups in different parts of Berlin and beyond. Particularly, we are working with and through the AKS Gemeinwohl project, which conducts studies on, connects, and mediates between civic initiatives and the administration of the Friedrichshain-Kreuzberg district; with the Raumstation collective, which is a group of activists focused on experimental spatial exploration, artistic and activist interventions, and critically reflective practices; and with the Häuser Bewegen cooperative, a newly established framework that brings together landlords and tenants with housing associations, companies, or the Tenement Housing Syndicate and seeks to facilitate the purchase of real estate for the Gemeinwohl.

As the Belgrade team noted, CMMM was started as the COVID-19 pandemic was unfolding and restricting our possibilities. This granted the authorities a reprieve after years of significant activist campaigns to claim space (e.g., Dragoner Areal in 2014 and Haus der Statistik in 2015) and large protests (e.g., the Mietenwahnsinn demonstration in 2019), which culminated in the Expropriate Deutsche Wohnen & Co. initiative and campaign in 2019 for a referendum on nationalizing the housing stock of large companies. Additionally, the general elections for the State of Berlin and the federal elections were on the horizon in 2021.

Through the CMMM project, our aim was to contribute to the broader scene of housing activism in the city by focusing on the need to establish and give a voice to narratives of dissent in dominant discourses and to consolidate and increase the pressure at political levels. We mapped the current legislation, policies, events, and hierarchies that shape the housing realities in Berlin in Section 5: How did we get here? 3 x timelines, Section 6: Who decides on what? governmental structures, participation tools, and political movements, and Section 7: What are we up against? main factors behind housing injustice. Section 8 demonstrates how mapping and visualization are common tools used by housing activists in Berlin. In Section 13 (2/2), we share an index of the major actors relevant to housing as part of an advocacy poster for reviving and re-framing the RPE instrument, which goes hand-in-hand with our “Buy Back Berlin!“ map. This map is the result of two workshops (described in Section 10 and Section 11), as well as a great deal of work in between.

During the process, we engaged with a variety of existing initiatives to negotiate an interface that maps and gives visibility to the multiplicity of (social) knowledge production bodies that are connected to Berlin’s Gemeinwohl. We focused in particular on the RPE as a pillar for a Gemeinwohl-oriented land policy (Bodenpolitik) both directly in connection with the issue of housing and beyond. We sought to connect small-scale initiatives and find ways to better relate their respective work. We realized that the concept of municipalism can be translated so as to give rise to new forms of political practice that open-up public administrations. However, unlike the scenes in Belgrade and Barcelona, the majority of anti-establishment activities have been channeled through actors situated within established political parties in Berlin, particularly the Greens (Bündnis 90/Die Grüne), the Left (Die Linke), and the Social Democratic Party (SPD).

As evident in different parts of this work and in contrast to Belgrade, yet similar to Barcelona, the issue of the right to the city and the right to housing has been politicized for many years, and many members of society are actively working to shift political discourses. For a decade now, the successive governments of Berlin have been taking some steps to reverse the laissez-faire neoliberal discourses that followed the reunification of the city and the country. However, their actions have just been a drop in the ocean, and the few steps forward are being reverted through narrow interpretations of the constitution by courts, as seen in the case of the rent cap law (Mietendeckel) and the application of the RPE. The subsidiarity of the Berlin government to the federal government is shackling, and the attitude of the recently elected government—which swept the demands articulated in the September 2021 referendum on nationalizing large stocks of housing under the carpet of committees that lack representation from the initiatives which set the referendum in motion—does not indicate that any radical change is to be expected in the foreseeable future. The road to achieving justice in how urban land and wealth are managed remains long and full of obstacles, yet we hope that our comrades and peers will be able to use the various materials and formats we made available in this work in our continued collective struggle.

Barcelona

Barcelona has always been a dynamic, political city, a place where different movements and organizations merge or are born. Since the fall of the Franco dictatorship, urban struggles have become an important part of the city’s life, with the first peek around the 1992 Olympics and the developments that ensued. Similar to Belgrade and Berlin, the 1990s saw a massive liberalization and deregulation of the economy and the shrinking role of the government in favor of making more space for capitalist investors. After years of buildup and triggered by the financial (mortgage) crisis that trickled over from the United States, the housing crisis in Barcelona has dominated and shaped social interventions since 2008 and is regularly mentioned by citizens as their most serious problem.

Figure 1.7

Remainders of internal walls of a demolished building in the Grácia district, Barcelona, 2012, to make way for a new development. Image by Andreas Brück.

With the reforms forced by the European Financial Stabilization Mechanism (which later became the European Stability Mechanism) as a precondition for the loans issued to the Spanish government, between 2013 and 2015 the housing emergency shifted away from massive foreclosures linked to mortgage defaults to a rental crisis. Today, about 40% of the inhabitants in Barcelona are renters, whereas the average in Spain is 25%, and the problem of unaffordability is writ large on every corner. Housing policies in Spain are far behind the rest of Europe in many regards. Buildings are often deteriorated (especially in the old part of the city where there has been an intentional lack of renovation). Prices are extremely high in comparison to income and are constantly inflating. Social housing accounts for only 1.6% of the total stock. Furthermore, laws provide for little protection for tenants, and the government has refused to regulate rent prices. A major cause of the acute housing conditions is the fact that Barcelona is one of the most popular touristic destinations in Europe, which leads to high demand for lodging and represents one of the greatest threats to locals when it comes to access to housing and the right to a non-commercialized neighborhood life.

With the anti-austerity 15-M Movement (Movimiento 15-M) that mobilized the streets throughout the country around the regional and local elections in Spain in 2011–2012, the political scene and power dynamics of the governing system changed. The established political parties were challenged, and protests gave rise to a diverse range of collectives organized in varying manners that pushed for alternatives. It was a crucial moment for rising grassroots initiatives like the Platform for People Affected by Mortgages (La PAH, Plataforma de Afectados por la Hipoteca), which was established in 2009 as they gained many supporters and members.

In the run-up to the general elections in 2015, a new municipalist movement brought together groups, activists, and ordinary people in many cities across Spain, and the newly formed Podemos party won 20.7% of the votes, making it the third largest party in the national parliament, just 1% behind the long-established Spanish Socialist Workers’ Party (PSOE, left) and 8% behind the People’s Party (PP, right). They won in dozens of localities and governed with the aim of implementing urgent progressive policies and changing the way politics is practiced. In relation to housing, they implemented regulations to restrict tourist accommodations, re-build the meager public housing stock, and create a mediation service to tackle and reduce eviction processes.

In Barcelona, the new government led by the Barcelona en Comú citizen platform, which was established in 2014, increased investments in public housing and implemented new social policies. However, evictions continued to be a daily phenomenon, and thus social movements for the right to housing have grown and multiplied. The different groups are coordinated and regularly call for people to stop evictions by staging protests at eviction sites. They organize actions against landlords and advocate for new laws and tangible social housing programs.

We, the CMMM Barcelona city team, are members of the Observatori DESC (ESCR Observatory) and are active in several other frames as well. Observatori DESC is a human rights organization with a hybrid character that aims to build bridges between urban social movements, the city administration, and academia, where our work is focused on pushing for more progressive laws and policies. Therefore, we support civil society campaigns, while at the same time disseminating information and data by conducting and publishing research, networking, and incorporating local, European, and international perspectives. Within the working track of the right to the city, a general objective of Observatori DESC is to prioritize and guarantee the social use of housing, which is a condition for dignified life. In our advocacy work, we push to provide more public and affordable housing, as well as innovative, human rights-based social policies to stop evictions. At the legislative and judicial levels, our main focus is on putting an end to abuses by big landlords (e.g., expulsions, harassment), reducing the high costs of housing (e.g., advocating for rent control measures), and illegalizing companies such as Desokupa, which carry out evictions by means of intimidation.

As noted by our colleagues in BGD and BLN earlier in this section, CMMM was started as the COVID-19 was unfolding and restricting our possibilities, which brought about a new wave of evictions in the city and Spain in general. This prompted the federal government to issue Royal Decree Law 11/2020 (which is set to expire in June 2023) and the Catalan government to issue Decree Law 37/2020 by (which expired in September 2022) to protect families economically affected by the pandemic against getting evicted, as explained at several points in this work. Nonetheless, in 2021, a total of 41,359 evictions were executed in Spain (of which 9,398 in Catalonia and 1,755 cases in Barcelona), which constituted a 30% increase compared to 2020. On average, there are seven evictions per day in Barcelona.

In light of what was mentioned above, within the framework of the CMMM project, Observatori DESC sought to examine with our network of housing organizations and movements how critical mapping has been used to document, mobilize, and advocate for a change in discourses on housing. In particular, we explored how to illustrate and record where and how evictions took and are taking place in the city and how to help organize the struggle against them. Along the same lines, we investigated ways to unpack the ownership structure of the housing stock (Who are the main landlords? Are they big companies or funds or individual owners?) as there is little information about this dimension and we need to identify who the “big evictors” are. Therefore, we started by mapping the current legislation, policies, events, and hierarchies that shape the housing realities in Barcelona in Section 5: How did we get here? 3 x timelines, Section 6: Who decides on what? governmental structures, participation tools, and political movements, and Section 7: What are we up against? main factors behind housing injustice. In Section 8, we share several examples of how mapping and visualization have been used in relation to housing in Barcelona. In Section 13(2/2), we share an index of the major actors relevant to housing as part of an informative and advocacy poster on the issue of evictions, which goes hand-in-hand with our “MapHab. Mapatge de la lluita per l’habitatge (Stop Evictions!)” map. This map is the result of two workshops conducted within the framework of this CMMM project (described in Section 10 and Section 11), as well as a great deal of work in between.

Initially, our goal was to offer the necessary resources for partner social movements to carry out their mapping tasks in response to the question of “who owns Barcelona?” and to reveal the assets of big landlords, which are camouflaged behind smaller sub-companies. As several participants in the first workshop outlined, we sought to create paths for civic human rights organizations and those vested in matters of public interest to access the cadaster data. However, the hurdles preventing this access forced us to reconsider, and thus we switched our approach to answering “who evicts in Barcelona?” From this perspective, we sought to (a) provide easier access to the information needed by activists and movements; (b) depict the evictions in Barcelona, which is a big concern in the city yet largely abstracted in numbers; (c) figure out who the landlords are who are ordering the highest number of evictions and clarify the variations across locations (neighborhoods); and (d) create socio-economic profiles of the evicted households. This information would allow for further steps, such as investigating the portfolios of the landlords and whether they have international connections or cross-comparing the evictions with the ownership structure in the city to determine whether big landlords are indeed causing the most evictions.

Establishing new perspectives and providing the type of information mentioned above would allow for a campaign to raise awareness about evictions in affected neighborhoods and to advocate for political regulations to tame owners with “bad practices,” such as frequent evictions. Indeed, the information presented on the two maps featured on the Stop Evictions! website can answer many of the questions of the activists and social movements working for the right to housing and to stop evictions. Although the current state of affairs at the legislative level and the conditions of the EU loans remain key challenges in ensuring that housing policies support human dignity, seeing the change in political programs inspires us to keep going. A decade ago, evictions and affordable housing were the exclusive domains of new municipalist platforms and activist groupings. Today, in one way or the other, they have been acknowledged by and are on the agendas of most political parties. We look forward to seeing how our Stop Evictions! map will grow and change over the coming months and years and how it and other materials provided in this work will serve the community of Barcelona.

section 2

Figure 1.8

The CMMM Process diagram, illustrating the various activities and components of the project.

The CMMM project was conceived at the Robert Bosch Stiftung (RBS) event “24 Stunden SPIELRAUM II - Urbane Transformationen gestalten” (24 hours Game Room II - Designing Urban Transformations) in December 2017 by a team of five: Julia Förster, Julita Skodra, Katleen De Flander, Natasha Aruri, and Andreas Brück. With the help of an RBS seed grant, our SPIELRAUM team developed and submitted an elaborate proposal in May 2018. Following review and a presentation at the RBS headquarters in Stuttgart, the commissioned evaluation committee endorsed the proposal and K LAB (TU Berlin) was awarded the grant. In summer 2019, the CMMM project started with Katleen and Natasha as postdoctoral researchers and coordinators (both in part-time positions), Andreas as project manager, and Julia as support and sounding board.

During the first few months, the focus lay on expanding the team to include mobilizers from the three cities. For Berlin (BLN), we were joined by Nija Maria Linke, Edouard Barthen, and Julian Zwicker; for Belgrade (BGD) by Iva Čukić, Jovana Timotijević, and Marko Aksentijević; and for Barcelona (BCN) by Irene Escorihuela Blasco, Laura Roth, and Carla Rivera. They brought the local collectives and organizations in which they are involved with them as collaborators for the project: AKS-Gemeinwohl and Raumstation for BLN, Ministarstvo Prostora (Ministry of Space) for BGD, and Observatori DESC for BCN.

After our CMMM team was formed, we jointly defined the thematic foci of the project within the broader context of municipalist movements. Given the nature of the activities of the members of the three city teams, we decided to focus on housing, with an open angle to be defined along the journey by each of the city teams in relation to the working agendas of their collectives. We held monthly meetings in which we discussed issues related to the project and beyond. Based on relevant events, changing conditions, and new information, we made consensus decisions on next steps and amended our agenda accordingly. As a practice-oriented project, the CMMM framework pivoted on collaborative formats that sought to combine and build on broader efforts within the various local movements.

In March 2020, we organized the international “Setting the Grounds” workshop with select guests, who later became our Advisory Committee members. We discussed various experiences and deliberated on key questions, many of which accompanied us throughout the lifespan of the project. The workshop helped each team start defining their concrete political target, on which they would focus in the following phases. A week after this workshop, Europe went on lockdown in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic.

In August, October, and November 2020, the BLN, BCN, and BGD teams respectively held their conceptualization workshops (what kinds of maps are needed?), which were attended by mixed groups of activists, professionals, and public servants. The teams presented initial ideas and discussed their validity, implementation potential, and next steps, as outlined in the workshop reports: Who buys Berlin?, Mapping property structures in Barcelona, and Housing burdens of social housing tenants and publicly owned land for the purpose of non-profit housing in Belgrade.

Between fall 2020 and summer 2021, with the feedback collected in the conceptualization workshops, the teams drafted initial analyses of the housing conditions in their cities. What were initially intended as short reports became extensive pieces that were created in a collaborative writing and production process between the city teams and K LAB, with feedback from some of the Advisory Committee members. These now include a timeline (Section 5) of key political events and legislations; a brief outline of the hierarchies of decision-making (Section 6) and main factors behind housing injustice (Section 7); relevant critical maps and visualizations (Section 8); and an index of major players (actors) in the three cities (Section 13). The latter is part of a poster illustration that explains the particular legislative procedure or instrument of focus for each city. As the CMMM project drew to an end in fall 2022, all texts were revised, updated, and finalized.

In spring 2021, the city teams organized design workshops, where they worked with participants to define the features and characteristics of the interactive maps they were creating. The purpose of the maps is to both inform and engage communities in the broader mobilizations toward tangible political change. As the workshop reports explain, in Barcelona they decided to focus on the continuing problem of Who evicts Barcelona?, in Berlin on the question of Commoning Berlin – but how? (with a focus on the vital yet weak instrument of Vorkaufsrecht, the right of preemption), and in Belgrade on Mapping the unaffordability of housing.

Between summer 2021 and fall 2022, in partnership with the Visual Intelligence team and with feedback from various collaborators, three interactive maps were developed: “Buy Back Berlin!,” “How (Un)affordable Is Housing in Belgrade?,” and “Stop Evictions!” in BCN. The maps vary in their structure and programming in accordance with their purpose. They were released online in Spring 2023.

In May 2022, after postponing twice due to COVID-19 surges in 2021, we were finally able to hold an International Gathering in BGD. As the CMMM team had changed slightly since the start of the project (see inner circle of the diagram above), this was the first face-to-face meeting for several of the team members. Next to the long over-due personal interaction, the meeting served to reflect on our joint journey so far and to decide on the final steps of the project. In addition, Irene and Julian contributed to the public discussion “Global housing struggles – experiences from Berlin, Barcelona, and Belgrade” organized by the Ministry of Space at the margins of the international gathering.

In summer 2022, a set of 28 “Thoughts on…” sound clips were extracted and curated from interviews (of about 1 hour each) that K LAB held with members of the city teams during the gathering in BGD. These are meant to introduce the voices of the people behind this CMMM project, provide glimpses of how they started, their experiences, their opinions regarding relevant issues, and explain how they keep going despite the many challenges. This introduction chapter ends with those clips.

As a spinoff of the CMMM project, in the week before the international gathering, the BGD team—together with K LAB—directed an excursion for students from three universities: TU Berlin, TU Darmstadt, and the University of Michigan. This BGD excursion was part of the TU Berlin master-level design studio Београд (Belgrade) 2041 - Futures of Post-Socialist Cities, which was taught by Iva, Jovana, and Andreas between April and July 2022. The course was designed to discuss current struggles and initiatives for city spaces in Belgrade, but also as an imaginative exercise regarding future scenarios for the “Belgrade Waterfront” site until 2041, which involved understanding the roles and interests of different stakeholders, creating a cost-benefit analysis, discussing further implications, and producing four alternatives (masterplans and scenarios) for Belgrade 2041.

Furthermore, some of the CMMM team members participated in the international Takhayali Ramallah workshop in September 2022, which brought together academics, practitioners, animation experts, and activists. The workshop focused on exploring alternative ways of seeing and sensing the city and worked toward defining new principles for a spatial management approach that accounts for social reproduction and climate change adaptation. One of the discussions revolved around whether and how a municipalist movement can be formed in Ramallah and was inspired by a presentation on the experience of the Ministry of Space (BGD team).

Between fall 2022 and winter 2023, we finalized the various project outputs featured on the cmmm.eu website. In addition to a printed book, the project’s website includes an array of interactive formats that allow visitors to explore, compare, and engage with the three cities. Ideally, individuals, initiatives, and movements will be able to make use of these materials long after they have been released.

To facilitate comparison and reach a broader audience, we have worked mainly in English, except for the BCN interactive map. However, in order for the work to be used broadly in the different contextual settings, key materials were translated into German, Serbian, Spanish and Catalan after the project was completed.

In 2023, we closed the project through three events. First was the podium discussion “MAP: Mobilizing Alternatives by and for People through Mapping and Maps“ which was held within the framework of the 4th International Social Housing Festival (ISHF), 7 to 9 June, in Barcelona. Then, in August 2023, Belgrade closed with the workshop “Critical mapping and visuals that mobilise for change” which took place within the “Terrestrial Forum / Horizons of Change” summer school, 22 to 27 August 2023. Finally, on 7 November 2023, a podium discussion that focused on the “Buy Back Berlin!” and "Stop Evictions" maps was held in Berlin.

CMMM Book

The CMMM book was initially written in English and it was published in summer 2024 by the Berlin Universities Publishing (BUP). Later, we translated selected sections into German, Spanish, Catalan, and Serbian (the latter includes about 80% of the book). The translations were published as well by the Berlin Universities Publishing in 2026. This subpages of this website feature much of the materials of the book but not everything.

section 3

Former Team members

We would like to acknowledge the contributions of the following persons who joined the CMMM team when the project started, but left it due to changing life conditions around the end of Phase 1 (early 2021) :

Edouard Barthen (Berlin city team)

Laura Roth (Barcelona city team)

Lýdia Grešáková (K LAB)

Tim Nebert (K LAB)

Further support

We are thankful to K LAB assistants Georg Müller and Karim Ghaleb for supporting the research and editorial works, and to the editor and proofreader Zachary Mühlenweg for his precision and flexibility.